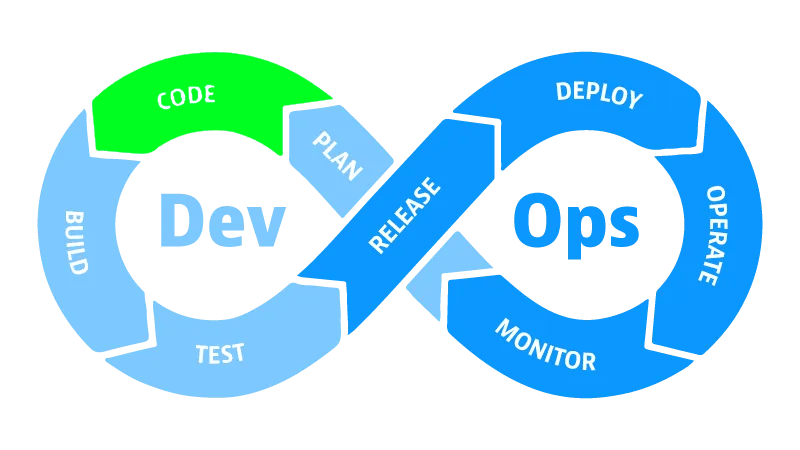

It’s that time again—another installment in our series showcasing the phases of the DevOps lifecycle in action. This time, we’re diving into the Code phase.

If you’re joining us for the first time, be sure to check out the beginning of the series here so you don’t miss out.

Let’s talk about the Code phase. When it comes to core software development, this is where the bulk of the work takes place. With our objectives laid out during the Plan phase, it’s time to start implementing.

But this phase involves far more than just writing features. We need to think about team collaboration, application maintainability, and leveraging automation to make our development time as effective as possible. Just as importantly, we want to extend many of the development practices our engineers use every day into our operations processes and team members.

Collaboration: The Backbone of Code

Effective collaboration is essential to any software development project—not just for sharing ideas and aligning on a common vision, but also for dividing tasks and reviewing each other’s work. To support this, we need a centralized repository where our code lives and where team members can contribute collectively. This is where Git serves as the backbone of code collaboration.

However, Git alone doesn’t solve collaboration—it’s a tool, and like any tool, it requires a strategy. That’s where branching strategies come into play. How can individual contributions be integrated effectively? How do we maintain quality and velocity as the team scales?

There are several popular branching strategies, with some of the most widely used being Trunk-Based Development, Git Flow, and GitHub Flow. Let’s take a closer look at each.

Branching Strategies

Trunk-Based Development involves all developers working on a single main branch, often called “trunk” or “main.” Small, frequent commits are encouraged to reduce merge conflicts and maintain a continuous integration flow. Branches are short-lived and merged back into the main branch frequently.

To support this approach, teams often use feature flags to manage incomplete features. This allows developers to integrate work early and often, without exposing unfinished functionality to users. The result is a fast-paced, collaborative workflow that minimizes overhead and keeps the codebase moving forward.

Git Flow introduces a more structured branching model, with dedicated branches for features, releases, and hotfixes. Development begins on the develop branch, while the main branch holds production-ready code.

Features are branched off of develop and merged back in when complete. When it’s time for a release, a release branch is created from develop and hardened through testing and bug fixes. Once ready, the release branch is merged into both main and develop—ensuring that any final changes are preserved in future development cycles.

This model suits teams with scheduled releases and complex workflows. It provides clear separation between development and production, making it easier to manage stability and coordinate deployments.

GitHub Flow is a lightweight, streamlined model focused on continuous delivery. It simplifies Git Flow by removing the develop and release branches, bringing the workflow closer to Trunk-Based Development.

In GitHub Flow, developers create short-lived feature branches off main, open pull requests for peer review, and merge changes after approval and testing. This approach emphasizes automation, rapid iteration, and frequent deployment.

GitHub Flow is ideal for teams that deploy often and value simplicity. It works especially well in environments where priorities shift quickly and where speed and adaptability are key.

| Model | Branching Complexity | Release Cadence | Best For | Main Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trunk-Based Development | Minimal | Continuous (daily/hourly) | Teams practicing CI/CD, fast-paced delivery | Encourages rapid integration and low overhead |

| Git Flow | High | Scheduled releases | Large teams with strict release schedules | Strong structure for managing multiple versions |

| GitHub Flow | Moderate | Continuous | Web apps and teams deploying frequently | Lightweight, easy collaboration via pull requests |

Bringing Work Together & Getting It to Production

At their core, each branching strategy revolves around two key elements: how we bring work together, and how we get code to production.

How do we bring work together?

Most branching strategies—including modern Trunk-Based Development—use a feature branch approach to implement new work. A feature branch is created off the main branch (often called main or master) and serves as a temporary workspace for development. Ideally, this branch is short-lived—lasting only a day or two.

Once the work is complete, the feature branch is merged back into the main branch via a pull request. Pull requests facilitate peer review and enforce branch policies, such as requiring automated tests to pass before merging. This process helps maintain code quality and ensures that contributions are properly vetted.

How do we get code to production?

This is where branching strategies diverge more significantly. Some teams use a release branch approach, where code is branched from the main branch and then tested and hardened separately. Bug fixes are made directly in the release branch and later merged back into main. Once the release branch is stable and production-ready, the code is deployed and the branch is deleted.

An alternative approach is continuous delivery, where code is deployed to production directly from the main branch after each merge—or after a small batch of merges. This model places greater emphasis on testing and validation before code is merged, but it dramatically accelerates the feedback loop. That speed is a core tenet of the DevOps philosophy.

My Preferred Strategy

Personally, I’m a big fan of GitHub Flow when the opportunity presents itself. I think it strikes a great balance between speed and structure. I prefer to push most of my testing and validation to the feature branch level. This encourages short-lived branches, frequent merges, and fast iteration—all of which depend on robust automation.

It also helps keep the main branch clean and stable, free from bugs and defects. This is the strategy I’ll be using for SaaStronaut.

Pair Programming: Real-Time Collaboration

Before we wrap up our discussion on collaboration, it’s important to highlight another powerful tool in this phase: pair programming.

Pair programming is a software development technique where two developers work together at a single workstation—or remotely using modern collaboration tools. One developer acts as the Driver, writing the code, while the other serves as the Navigator, reviewing the code in real time and thinking strategically about its direction.

The Navigator identifies opportunities for improvement, anticipates potential challenges, and helps guide the overall approach. This frees the Driver to focus on implementation details. The two developers switch roles frequently to maintain engagement and balance.

Pair programming is incredibly effective for several reasons:

- It promotes immediate knowledge sharing, ensuring both developers understand the work being done.

- It provides real-time peer review, which significantly improves code quality.

- It broadens the skillsets of both participants by exposing them to different problem-solving approaches and coding styles.

If you haven’t explored pair programming in your development efforts, I highly encourage you to give it a try.

Maintainability: Writing Code for the Long Haul

Typically, we think about maintainability in the long term—ensuring that code can still be worked on years down the road without being crushed by complexity or technical debt. We want future developers to understand our application even if we’ve long since moved on to other projects.

But maintainability is just as important in the short term. Because our DevOps process is cyclical, maintainability means ensuring each pass through the cycle is as frictionless as possible. As we add new features and modify existing ones, we need to set ourselves up to run through tens, hundreds, or even thousands of iterations efficiently.

Developing maintainable software systems is a deep topic—far too broad to fully cover in this article alone. But there are two particular techniques worth highlighting: one at the architectural level, and one at the implementation level. Let’s start with structuring our applications as Microservices.

Microservices Architecture

True to its name, a microservices architecture revolves around several small, discrete services, each with its own distinct responsibilities. This supports the design principle of Separation of Concerns, reducing component complexity by making each service single-responsibility and inherently smaller than a monolithic application.

Each microservice exposes an API that allows other services to interact with it. This means services can be modified independently—as long as they adhere to their API contracts, dependent services remain unaffected.

This abstraction offers technical flexibility as well. Different teams might own and specialize in specific services, allowing them to tailor implementations to their needs. One team might use C# for Service A, while another uses Rust for Service B. Service B could be completely reimplemented, and Service A wouldn’t need to care—only the API matters.

This independence can extend to code repositories too. Each microservice might live in its own Git repository, with its own branching strategy and release cadence. This is especially powerful when different teams own different services and need to scale independently.

Of course, microservices aren’t without tradeoffs. They introduce system complexity in exchange for reduced component complexity. Communicating via APIs is inherently more involved than calling methods within a monolith. Network latency, connectivity, and service orchestration become new challenges. Deploying and maintaining ten microservices is more work than managing a single application.

It’s important to weigh these tradeoffs carefully. Microservices are a powerful tool—but like any tool, they’re best used when the job calls for them.

As mentioned in our last article, we’ll be building SaaStronaut as a microservice-based system. This gives us the flexibility to explore different frameworks and languages across components, and to leverage diverse infrastructure and platform options for deployment.

Linting: Enforcing Consistency

The second maintainability concept I want to highlight is linting. Linting is the process of analyzing code to identify potential errors, inconsistencies in style or structure, and deviations from coding standards. This is done using automated tools called linters.

A linter might flag a variable that could be null, prompting a null check to prevent future bugs. It might enforce naming conventions, whitespace usage, or class layout to ensure consistency across the codebase.

Linting is essential for maintainability, especially in collaborative environments. It helps keep code consistent even when many developers are contributing. This makes it easier to work across different areas of a system and smooths the onboarding process for new team members.

Linting is typically done both locally—on the developer’s machine—and as part of the build pipeline. This ensures fast feedback and quick correction, rather than relying solely on peer review during pull requests. Before each commit, developers can lint their work to ensure it meets stylistic and structural standards.

Infrastructure as Code (IaC): Dev Meets Ops

When we talk about the Code phase, we’re not just referring to application code. True to the DevOps promise, this is also where Operations gets involved. It’s our opportunity to define infrastructure as code and apply many of the same development strategies we’ve already discussed.

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) is the practice of provisioning and managing IT infrastructure using code instead of manual processes or interactive tools. This means defining resources like networks, servers, and databases in a structured format that can be consumed by a system to create, update, or remove infrastructure components.

IaC emerged in response to the rise of cloud computing, which introduced scalability challenges that many organizations hadn’t previously faced. A wave of new tools followed—focused on configuration management and infrastructure automation—leading to what we now consider modern IaC.

By codifying infrastructure, we can apply the same practices we use for application code:

- Version control and branching

- Pull requests and peer reviews

- Linting and testing

- Automated pipelines

IaC also enhances scalability. By parameterizing deployments, we can reuse the same code across multiple systems and environments—reducing duplication and increasing efficiency.

Wrapping Up

The Code phase of DevOps is far more than just writing application logic—it’s the heartbeat of collaboration, maintainability, and automation. In this phase, we bring together the planning and strategy laid out earlier and begin transforming ideas into working software. Whether through Git-based workflows, branching strategies like GitHub Flow or Trunk-Based Development, or real-time techniques like pair programming, the Code phase is where teamwork and tooling converge to drive progress.

We also explored how maintainability plays a critical role—not just in the long-term health of a system, but in the short-term agility of our DevOps cycles. Architectural choices like microservices empower teams to scale and specialize, while implementation-level practices like linting ensure consistency and clarity across the codebase. These techniques help us iterate faster, onboard more smoothly, and keep technical debt in check.

Finally, we extended the concept of “code” beyond application logic to include infrastructure itself. With Infrastructure as Code, operations become an integral part of the development process, enabling version control, automation, and repeatability across environments. This holistic approach is what makes DevOps so powerful: it unifies development and operations through shared practices, tools, and philosophies—all starting with how we write, manage, and deliver code.

That was a lot! It should come as no surprise that there’s so much going on in the Code phase of DevOps. In fact, there’s so much that I’ll be splitting this breakdown into two parts.

We’ll wrap up the theory portion here, and next time we’ll explore applying these concepts in our SaaStronaut project.

Thanks for coming along for the ride—and stay tuned for Part 2!